A Deep Dive into Pilates Reformer Exercise

Share

So, what exactly is a Pilates reformer workout? At its core, it's a method that uses a specialized apparatus—with its sliding carriage, springs, and straps—to build deep muscular strength, cultivate flexibility, and sharpen the neuromuscular connection between mind and body.

This machine is brilliant because it can provide either spring-loaded resistance to challenge musculature or assistance to support proper joint alignment and muscle activation. The result is a low-impact, full-body session focused on control and precision, targeting the deep stabilizing muscles that are often neglected in conventional workouts.

The Anatomy of a Reformer Workout

Before pushing off the footbar, it's crucial to understand the biomechanical relationship between the machine and your body. A Pilates reformer isn’t just equipment; it’s a tool that provides tactile feedback, teaching you how to initiate movement from your deep core—what Joseph Pilates called the "powerhouse." This synergy between human anatomy and machine is what makes every single pilates reformer exercise so effective.

And it seems the world is catching on. The global Pilates reformer market was valued at around USD 7.65 billion in 2025 and is expected to nearly double by 2035. That’s a huge shift toward more mindful, anatomy-focused fitness.

Connecting the Machine to Your Musculature

The true genius of the reformer lies in its components, each designed to engage specific muscle groups. The springs, for instance, create a constant, controlled tension that forces muscles to work through their full range of motion—both during shortening (concentric contraction) and, equally important, during lengthening against resistance (eccentric contraction).

- The Carriage: This moving platform creates an unstable surface, forcing deep core stabilizers like the transverse abdominis and multifidus to fire continuously to maintain spinal and pelvic stability.

- The Springs: With adjustable tension, you can either challenge global movers like the quadriceps and latissimus dorsi or provide lighter assistance to isolate smaller, deep postural muscles.

- The Footbar & Straps: These anchor points allow you to push or pull, creating movements that decompress the spine and strengthen the appendicular skeleton (arms and legs), all while maintaining a stable core.

To understand how these components target your anatomy, let's break it down.

Table: Key Reformer Components and Their Anatomical Purpose

This table clarifies how each part of the reformer is engineered to engage or support specific areas of your body, helping you understand the biomechanical "why" behind each movement.

| Reformer Component | Primary Function | Anatomical Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Carriage | Creates a dynamic, unstable surface that moves with spring tension. | Engages deep core stabilizers (transverse abdominis, multifidus) to maintain trunk stability. |

| Springs | Provide adjustable, progressive resistance or assistance for movements. | Targets global movers (quads, glutes, lats) and deep stabilizers, depending on the exercise. |

| Footbar | A stationary bar for feet or hands to push against. | Primarily engages the lower body (glutes, hamstrings, quads) and helps establish pelvic stability. |

| Straps (with loops) | Used for pulling movements with hands or feet. | Focuses on upper body (lats, deltoids, biceps, triceps) and lower body (adductors, abductors, hamstrings). |

| Shoulder Blocks | Provide a secure point to press against, preventing sliding. | Helps maintain thoracolumbar alignment and allows for safe force production from the legs and core. |

As you can see, every piece has a biomechanical purpose, working in concert to create a truly integrated, full-body workout.

Your Powerhouse: The Foundation of Movement

At the center of every movement on the reformer is your powerhouse. This is not just the superficial rectus abdominis ("six-pack" abs). It's a system of deep muscles that function as a dynamic corset, supporting your spine and pelvis.

A strong powerhouse is the secret to moving efficiently, powerfully, and without pain—not just on the reformer, but in your daily life. It is your body's intrinsic stabilization system, supporting the entire trunk from the inside out.

The key muscles are the transverse abdominis (the deepest abdominal layer), the muscles of the pelvic floor, the diaphragm, and the deep spinal multifidus muscles. Learning to co-contract this system is the primary goal of your reformer practice.

This deep muscular connection is the secret behind all effective pilates exercises for core strength. When these muscles activate correctly, you protect the lumbar spine, improve posture, and generate power from your center, making every exercise safer and more impactful.

Mastering Foundational Reformer Movements

Now that you have a solid grasp of your powerhouse anatomy, it’s time to apply that knowledge to movement. The foundational Pilates reformer exercises are designed to teach your body how to initiate movement from its center, creating a stable foundation for more complex choreography.

The focus is less on the external shape of the exercise and more on the deep muscular control you maintain throughout. This process—connecting the machine, to your anatomy, to the movement—is the core principle of a successful practice.

This visual breaks it down: a great reformer exercise starts with understanding the equipment, connecting it to your internal anatomy, and only then executing the movement with precision.

The Footwork Series Unpacked

Footwork is nearly always the first exercise in a reformer session because it’s a powerful diagnostic tool. It activates the powerhouse, encourages proper lower limb alignment, and establishes the neuromuscular patterns for the workout. It is far more than just pushing the carriage.

As you press the carriage out (hip and knee extension), the primary movers are your quadriceps and gluteus maximus. The critical work, however, is maintaining a neutral pelvis. To prevent lumbar hyperextension (arching the lower back), you must engage your transverse abdominis (TVA) by drawing the navel toward the spine.

Then, as you control the carriage's return (hip and knee flexion), your hamstrings and glutes work eccentrically to resist the spring tension. Mastering this controlled return is where true functional strength is built.

Pro Tip: Imagine your pelvis is a bowl of water that you can't let spill. This cue helps activate the deep core musculature to maintain a stable, neutral pelvic position, preventing the lumbar erector spinae muscles from overworking.

Activating the Right Muscles in Footwork

Let's get specific about the muscular engagement during this foundational series.

- On the Toes: This position targets the quads while requiring deep engagement from the ankle plantar flexors (gastrocnemius and soleus) for ankle stability.

- On the Arches (Pilates V): With heels together and toes apart (slight external rotation of the femur), the focus shifts medially. This variation activates the inner thigh muscles (adductors) and the external hip rotators, particularly the gluteus medius, to stabilize the femur and prevent knee valgus (knees collapsing inward).

- On the Heels: Pushing from the heels fully engages the entire posterior chain. The gluteus maximus and hamstrings are the prime movers, building power essential for activities like running and climbing stairs.

If you're just starting out, our guide on Pilates at home for beginners has some great tips for building this mind-body connection right from day one.

The Hundred: An Anatomical Deep Dive

The Hundred is the signature Pilates exercise for abdominal endurance. While it appears to be a simple crunch, the objective is to maintain a deep, isometric contraction of the TVA for all 100 breaths.

To perform this correctly, the lumbar spine must remain imprinted on the carriage. This requires a slight posterior pelvic tilt, maintained by the lower abdominals and obliques. A common error is straining the neck; the thoracic flexion (lift of the head and shoulders) should originate from the upper rectus abdominis, creating a "C-curve" in the thoracic spine while the lumbar spine remains stable.

The vigorous arm pumping introduces a dynamic challenge, forcing the core to stabilize the torso against the movement of the limbs—a true test of dynamic stability.

Elephant: Lengthening and Strengthening

Elephant is a brilliant exercise for teaching spinal articulation while strengthening the core and lengthening the posterior chain. Standing on the carriage, you press the heels down and use the deep abdominals to flex the spine and pull the carriage inward.

The primary goal is to initiate the movement from the deep core, not by flexing the knees or using momentum. The TVA and obliques act as the engine that closes the springs. As you press the carriage away, you create an eccentric load on the hamstrings and gastrocnemius, which is key to developing flexible strength.

Leveling Up: Advancing Your Practice with Intermediate Exercises

So, you've mastered the fundamentals and can feel that deep core connection activate instinctively. Fantastic. Now you’re ready to progress beyond the basics and explore more dynamic, challenging reformer choreography.

Intermediate exercises are about integration. They demand more from the body, requiring it to maintain core stability while the limbs and spine move through more complex, multi-planar patterns. This skill builds true functional strength, translating to better posture and more efficient movement in daily life.

Finding Flow: The Art of Spinal Articulation in Short Spine Massage

Short Spine Massage is a classic reformer exercise that requires immense abdominal control. The primary goal is sequential spinal articulation—the ability to peel the spine off the carriage vertebra by vertebra and then lay it back down with equal control. It provides an incredible stretch for the erector spinae muscles and is a formidable workout for the entire core.

The movement must be initiated from the lower abdominals and obliques. The main challenge is resisting the use of momentum from the legs. As you lift, the transverse abdominis (TVA) must work intensely to support the lumbar spine. The return journey is equally crucial; laying the spine down segmentally is what truly activates the deep multifidus muscles along the vertebrae.

I see this all the time: as the work gets harder, tension creeps into the neck and shoulders. Try to keep the effort in your powerhouse. Focus on maintaining cervical length and allowing the shoulders to relax, using the shoulder blocks for stability, not bracing.

Building a Dynamic Plank with the Long Stretch

If you think a floor plank is challenging, a plank on a moving carriage introduces a new level of instability. The Long Stretch transforms a static hold into a dynamic, full-body stability exercise. You must maintain a perfect plank position while the core and shoulder girdle control the carriage's movement.

The secret to a solid Long Stretch is the co-contraction of the latissimus dorsi and the contralateral obliques. This muscular "sling" creates a stable trunk and prevents the pelvis from sagging (lumbar extension) or hiking (lateral flexion). As you push the carriage out, your anterior deltoids and pectoralis major are active, but the core must work harder to maintain stability on the moving surface.

Beginner vs. Advanced Exercise Progression

Understanding how a foundational move evolves is key to safe progression. It's not about jumping to the hardest version; it's about building the requisite strength and control at each stage. This table breaks down how a basic exercise can be advanced, highlighting the new anatomical challenges.

| Foundational Exercise | Primary Muscles Worked | Advanced Variation | Added Anatomical Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Footwork | Quads, Glutes, Hamstrings, TVA | Single-Leg Footwork | Increases demand on pelvic stabilizers (gluteus medius) to prevent hip hiking or rotation. |

| Pelvic Curl | Glutes, Hamstrings, Lower Abs | Short Spine Massage | Requires deep abdominal strength to lift the entire pelvis and legs, plus controlled spinal articulation. |

| Mat Plank | TVA, Obliques, Rectus Abdominis | Long Stretch on Reformer | Challenges dynamic stability of the shoulder girdle (serratus anterior, lats) and core against a moving surface. |

As you can see, the progression from beginner to advanced is a shift from simple muscle activation to complex, full-body integration and dynamic motor control. Each step prepares your neuromuscular system for the next, allowing you to build strength intelligently and without injury.

Anatomical Troubleshooting for Common Mistakes

We’ve all been there. You’re performing an exercise when an instructor provides a cue that creates an "aha" moment. Suddenly, the muscular engagement deepens. But old motor patterns often return.

Understanding the anatomical reason behind common form errors is the key to making corrections permanent. When you learn to identify these patterns in your own body, you move beyond mimicry. You refine your practice from an internal, kinesthetic awareness, making every pilates reformer exercise more effective.

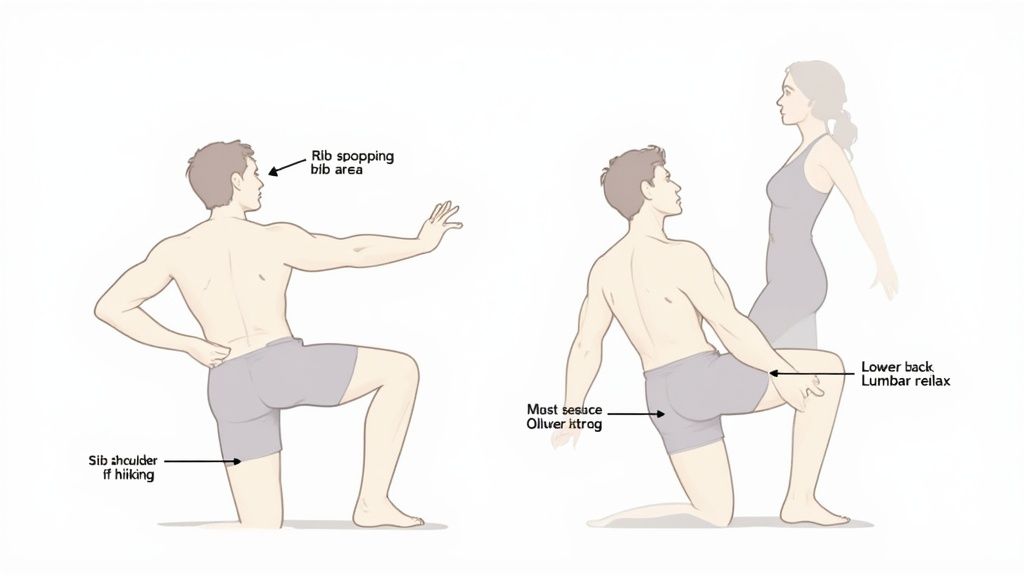

Decoding Rib Popping and a Weak Core

Have you ever heard the cue to "knit your ribs together"? It’s one of the most common Pilates corrections because it addresses thoracic extension, or "rib popping," where the anterior rib cage flares upward, especially during movements like Footwork or overhead arm exercises.

This is a clear sign that the deep core muscles are disengaged. Anatomically, it means your transverse abdominis (TVA) and your internal and external obliques are not stabilizing your torso. Your rectus abdominis might be working, but without the corset-like support of the deeper layers, your rib cage disconnects from your pelvis.

Corrective Cue: Before initiating movement, perform a full exhale. Feel your anterior ribs soften down and draw medially toward your pelvis. Imagine zipping up a vest that connects your lowest rib to your anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). This thought alone engages the obliques and TVA.

Shoulder Hiking and Overactive Traps

Does tension accumulate in your neck and shoulders during arm work or even core exercises like The Hundred? This is almost always due to shoulder elevation, the habit of letting the shoulders creep toward the ears.

Anatomically, this indicates that the upper trapezius muscles are overactive, performing a job they aren't designed for. The muscles that should be stabilizing your scapula, like the serratus anterior and the lower trapezius, are likely inhibited or underactive.

- To Fix It: Actively create space between your earlobes and the acromion process (top of the shoulder). A useful visualization is to imagine your scapulae gliding down your ribcage into your back pockets. This simple shift engages the latissimus dorsi and lower trapezius, creating a more stable base for any appendicular movement.

Lower Back Strain and Muscular Imbalances

That nagging pinch in the lower back is often a symptom of an imbalance elsewhere. The strain occurs when the lumbar spine hyperextends to compensate for weakness or tightness in other areas.

The common culprits are underactive gluteus maximus and tight hip flexors (psoas and iliacus). When the glutes fail to act as primary hip extensors, the lumbar erector spinae muscles compensate, creating a stressful arch. Tight hip flexors exacerbate this by pulling the pelvis into an anterior tilt, increasing the lordotic curve of the lumbar spine.

The solution is not to focus on the back itself, but to activate the glutes and release the hip flexors. This builds long-term support and protection for the spine.

How to Build a Balanced At-Home Reformer Workout

Knowing your anatomy is one thing; consistency is another. Building a smart, balanced routine at home is key to maximizing results. This is about more than just stringing exercises together; it's about thoughtful sequencing to properly prepare, challenge, and restore the body's tissues.

The secret to an effective at-home pilates reformer exercise plan is structure. A well-designed workout flows logically, preparing muscles for more demanding work and finishing with movements that restore length and flexibility. This approach minimizes injury risk and accelerates progress.

The Art of Smart Sequencing

Structure your workout into three distinct parts: warm-up, main sequence, and cool-down. Each phase serves a specific physiological purpose, guiding your body through a safe and effective progression.

-

Warm-Up (5-10 minutes): This phase is about neuromuscular activation. Begin with foundational movements like the Footwork series to increase synovial fluid in the joints and activate the glutes, hamstrings, and deep core stabilizers.

-

Main Sequence (15-25 minutes): This is the core of your workout. Build intensity with exercises that challenge core endurance, like The Hundred, or integrated movements that demand full-body motor control, such as the Long Stretch series.

-

Cool-Down (5 minutes): Conclude by lengthening the muscles you just contracted. Stretches like the Mermaid are perfect for releasing the obliques, quadratus lumborum, and intercostal muscles, while gentle spinal articulation helps restore mobility.

Sample At-Home Workouts

Here are two sample routines for different goals. Always listen to your body and adjust spring tension as needed. Sometimes, a lighter spring increases the core challenge by reducing external support and forcing greater internal stabilization.

A common myth is that heavier springs always equal a harder workout. For many core-focused exercises, removing a spring forces your deep stabilizers to work overtime to control the carriage. That's where real neuromuscular change occurs.

Workout 1: The 20-Minute Core Ignition

This quick routine is designed to activate your powerhouse, leaving you feeling centered and strong.

| Exercise | Sets/Reps | Anatomical Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Footwork Series | 10 reps each position | Wakes up the posterior chain and establishes core connection. |

| The Hundred | 100 pumps | Builds core endurance and dynamic torso stability. |

| Short Box Series (Round Back) | 8-10 reps | Targets deep abdominals (TVA) and promotes spinal articulation. |

| Elephant | 8 reps | Stretches hamstrings while strengthening the core. |

| Mermaid Stretch | 3-4 reps per side | Lengthens the obliques, QL, and intercostal muscles. |

Workout 2: The 30-Minute Full-Body Flow

This workout provides a more comprehensive session, moving through all planes of motion to challenge the entire body.

- Warm-Up: Footwork (all variations) and Pelvic Curls.

- Core & Spine: The Hundred and Short Spine Massage.

- Strength & Integration: Long Stretch series and Scooter.

- Flexibility: Side Splits and Mermaid Stretch.

For those building a home studio, exploring different types of Pilates equipment for home use can add variety and depth. Progressing your workout involves knowing when to increase spring tension or advance to a more complex variation, ensuring your practice evolves with your strength.

Your Top Pilates Questions, Answered

As you deepen your Pilates practice, questions about the method's principles will arise. Understanding the "why" is as important as the "how" for building a safe and effective practice. Let's address some common inquiries.

How Often Should I Be on the Reformer?

For beginners, consistency is paramount. Aim for 2-3 sessions a week.

This frequency allows sufficient time for neuromuscular adaptation, giving your deep stabilizing muscles, like the transverse abdominis, time to recover and strengthen. You are building new motor patterns. As your strength and proprioception improve, you can increase frequency, but always prioritize recovery and listen to your body's feedback.

Can I Still Do Pilates if I Have Back Pain?

Many people seek out Pilates for back pain because the method focuses on strengthening the deep core muscles that support and decompress the spine.

However, it is essential to obtain clearance from your doctor or physical therapist first.

Once cleared, work with a qualified instructor who understands your condition. They can provide modifications to ensure every movement is performed within a pain-free range of motion, with a primary focus on maintaining a neutral spine and avoiding compensatory patterns.

What’s the Real Difference Between Mat and Reformer Work?

The primary differentiator is the spring system on the reformer.

On the mat, you work against gravity with your own body weight, which requires immense internal control and stabilization.

The reformer's springs introduce a new dynamic. They can be set to assist movement (beneficial for rehabilitation or learning new patterns) or to add resistance. This versatility allows for more specific muscle targeting. Furthermore, the moving carriage creates an unstable surface that constantly challenges your proprioceptive system and stabilizer muscles in a way the static floor cannot.

Ready to bring this anatomy-focused approach into your own home? The WundaCore collection, designed by founder Amy Jordan, translates these core principles of intelligent movement into a system you can use anywhere. Our patented props and hundreds of on-demand classes are here to guide you.