How to Prevent Lower Back Pain: An Anatomy-Based Guide to Lasting Relief

Share

If you want to sidestep lower back pain, you have to think beyond just "lifting with your knees." Real prevention is about building a strong, intelligent core that acts as an internal support system for your spine. It's this deep anatomical foundation that creates a resilient back capable of handling whatever life throws at it, from carrying groceries to hitting a new personal best in the gym.

Getting to Know Your Lower Back Anatomy

Before we can protect the lower back, we need to understand its structure. Your lumbar spine—the five vertebrae labeled L1 to L5—is the central pillar supporting your entire upper body. It's an incredible piece of biomechanical engineering, built for both strength and mobility, but this complexity also makes it vulnerable to injury.

This system is far more than just bones. It's a dynamic interplay of vertebrae, shock-absorbing intervertebral discs, a network of sensitive nerve roots exiting the spinal cord, and layers of muscle. When every component functions in harmony, your spine feels stable and pain-free. But if one anatomical piece is weak or misaligned, the entire system feels the strain.

Your Body's Built-In Corset: The Deep Core Musculature

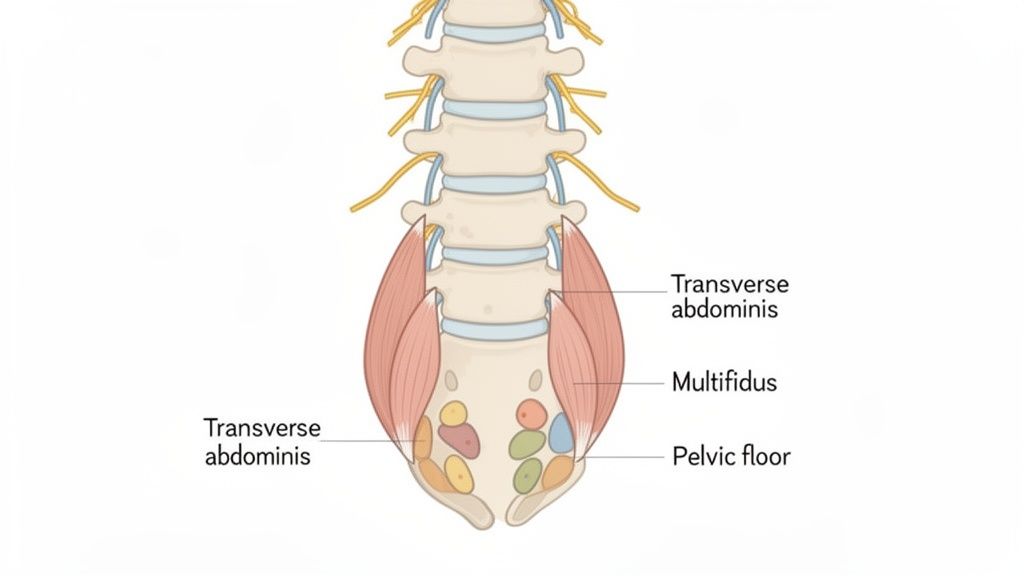

When most people hear "core," they picture the rectus abdominis—the "six-pack" muscle. But the true MVPs for spinal stability are much deeper muscles you can't see, which are absolutely essential for preventing back pain.

Imagine a supportive, muscular corset wrapping around your entire midsection, from your spine to your abdomen. That's your deep core. Let's meet the key anatomical players.

To truly grasp how these muscles work together, it's helpful to see their specific roles laid out.

Your Spine's Support System: Key Players and Their Roles

| Anatomical Component | Primary Function | Why It Matters for Pain Prevention |

|---|---|---|

| Transverse Abdominis (TVA) | The deepest abdominal muscle, its fibers run horizontally. It acts like a wide belt, creating intra-abdominal pressure to stabilize the pelvis and lumbar spine. | A strong TVA is your first line of defense. It co-contracts with other deep muscles before you move, bracing the spine to handle the impending load. |

| Multifidus | Small, powerful muscles running along the spine, connecting individual vertebrae. | These provide crucial segmental stability, preventing the small, shearing movements between vertebrae that can irritate facet joints and discs. |

| Pelvic Floor | A muscular sling at the base of the pelvis, forming the "floor" of the core canister. | A functional pelvic floor helps manage intra-abdominal pressure, which is critical for stabilizing the lumbopelvic region during exertion. |

When this "corset" is strong and you know how to engage it properly, it protects the passive structures of your spine (bones and discs) from excessive strain. It anticipates movement and prepares your spine for the load. Without it, the larger, superficial muscles (like the erector spinae) must overwork, leading to fatigue, strain, and pain. You can learn more about how to target this deep system in our guide on what muscles Pilates works.

The Building Blocks of Your Spine: Vertebrae and Discs

Your spine is a column of bones called vertebrae. Sandwiched between each one is a tough, fibrocartilaginous cushion—the intervertebral disc. These discs have a tough outer layer (annulus fibrosus) and a jelly-like center (nucleus pulposus). They act as your body's natural shock absorbers, compressing and expanding as you move. To stay plump and effective, they rely on a process called imbibition to absorb nutrients and water.

A sedentary lifestyle or chronically poor posture places uneven, sustained pressure on these discs. Over time, they can dehydrate, lose height, bulge, or even herniate, where the nucleus pulposus pushes through the annulus fibrosus and can press on a nearby spinal nerve. That nerve impingement is often the source of sharp, radiating pain.

Back pain is a massive global issue, and it's not going away. In 2020, a staggering 619 million people worldwide were dealing with low back pain, making it the top cause of disability. Experts project that number will climb to 843 million by 2050, mostly due to our aging population.

When you understand the anatomy, the path to prevention becomes much clearer. By strengthening your "natural corset" and moving with awareness, you're directly supporting the discs, vertebrae, and nerves that are so critical to a healthy, pain-free life.

Mastering Your Everyday Posture and Ergonomics

Understanding the anatomy behind lower back pain is one thing, but applying that knowledge biomechanically in daily life is where prevention truly happens. Good posture isn't about rigid stiffness; it's about maintaining your spine's natural curves—the gentle lordotic curve in your lumbar spine and the kyphotic curve in your thoracic spine—so your deep core muscles can function optimally and distribute forces evenly across your vertebrae and discs.

When this alignment fails, gravity's forces are no longer distributed efficiently. The common forward head posture, for example, increases the load on the cervical spine, creating a chain reaction that forces the lumbar spine to compensate. The good news is that small, consistent ergonomic adjustments can stop this cascade.

Your Ergonomic Workspace Blueprint

For many, the desk is where healthy spinal alignment breaks down. Hours spent hunched over a laptop can reverse the natural lordotic curve of the low back, placing immense pressure on the posterior aspect of the intervertebral discs. An ergonomic setup isn’t a luxury; it’s a non-negotiable for spine health.

First, your chair must support the lumbar curve. If it doesn't, a dedicated lumbar roll is essential. Your feet should be flat on the floor, with your hips and knees ideally at a 90-degree angle. This keeps the pelvis in a neutral position.

Next, your monitor. The top of the screen should be at or just below eye level. This simple fix prevents flexion in the cervical and upper thoracic spine, which helps keep the entire spinal column in better alignment.

- Keyboard and Mouse: Position them to allow your elbows to be bent at approximately 90 degrees with relaxed shoulders. This prevents tension in the trapezius and shoulder girdle that can radiate down.

- Move Every Hour: Even a perfect setup can't negate the physiological effects of being static. Movement facilitates the imbibition process, allowing your spinal discs to rehydrate and receive nutrients. Set a timer to stand, stretch, and walk for a few minutes hourly.

The goal of ergonomics is to align your environment with your body's anatomy, not force your anatomy to conform to a poorly designed environment. This neutral alignment minimizes stress on muscles, ligaments, and the sensitive facet joints of your lower back.

Posture Beyond the Desk

Your spine's health is determined by your habits 24/7. How you stand, sleep, and lift objects all have a massive biomechanical impact on your lumbar region.

When standing, avoid locking your knees (hyperextension). This can cause an anterior pelvic tilt, exaggerating the lumbar lordosis and compressing the facet joints. Maintain a slight bend in your knees and engage your glutes and lower abdominals to support a neutral pelvic position.

The Art of Safe Lifting and Sleeping

Lifting is a high-risk activity for the lumbar spine if performed incorrectly. The phrase "lift with your legs" is a simplification of a more complex biomechanical principle: use the powerful hip extensors (glutes and hamstrings) while maintaining a neutral spine.

Here's the correct anatomical sequence:

- Get Close: Position yourself near the object to reduce the lever arm's length, minimizing torque on your spine.

- Brace Your Core: Co-contract the transverse abdominis and multifidus to create intra-abdominal pressure and stabilize the lumbar spine.

- Hinge, Don't Round: Initiate the movement by hinging at the hips, not by flexing the lumbar spine. Keep your back straight.

- Drive Through Your Heels: Engage your glutes and quadriceps to power the lift, keeping the object close to your center of gravity. Crucially, do not twist the lumbar spine while under load.

Even your sleeping position matters. Sleeping prone (on your stomach) can force the lumbar spine into extension and the cervical spine into rotation for hours. The best positions are supine (on your back) with a pillow under your knees, or on your side with a pillow between them. Both positions help maintain a neutral alignment of the pelvis and spine, allowing the paraspinal muscles to relax and recover.

Building a Resilient Core with Targeted Exercises

Once you've optimized your daily posture, the next layer of protection comes from building active strength from the inside out. A resilient core isn't about the superficial rectus abdominis; it’s about creating a muscular support system that actively braces the lumbar spine. The goal is to train the deep stabilizing muscles we discussed earlier to fire automatically.

Think of it like this: good posture is a well-designed bridge. A strong core provides the high-tension steel cables that make that bridge unshakable against dynamic forces. The goal is to train these deep muscles to co-contract automatically, creating a natural "corset" that protects your lower back without conscious thought.

Waking Up Your Deep Core Muscles

Before you can strengthen a muscle, you must establish a neuromuscular connection. This is especially true for your transverse abdominis (TVA) and multifidus. These foundational exercises are about precision, not power.

- Pelvic Tilts: Lie supine with knees bent. Gently press your lower back into the floor by contracting your lower abdominal muscles (posterior pelvic tilt), then slowly release to a neutral spine. The movement should be small and isolated to the lumbopelvic region.

- Heel Slides: In the same position, maintain a neutral spine and engage your TVA. Slowly slide one heel away from you along the floor. The core's job is to prevent any movement—rocking, tilting, or arching—in the pelvis and lumbar spine.

These simple moves teach lumbopelvic dissociation and stabilization, the absolute bedrock of preventing lower back pain. For a deeper dive, check out our guide on how to activate the transverse abdominis.

Progressing to Dynamic Stability

Once you can consciously activate your deep core, the next step is to challenge its ability to stabilize against limb movement. These exercises mimic the demands of real-world activities in a controlled setting.

Bird-Dog:

Start in a quadruped position, hands under shoulders, knees under hips.

- Engage your core to create a flat, stable back.

- Simultaneously extend your right arm and left leg, keeping your hips and shoulders level with the floor. The multifidus and TVA must work hard to prevent rotation in the spine.

- Focus on creating length from fingertips to toes, maintaining a neutral spine.

- Return to the start with control and switch sides.

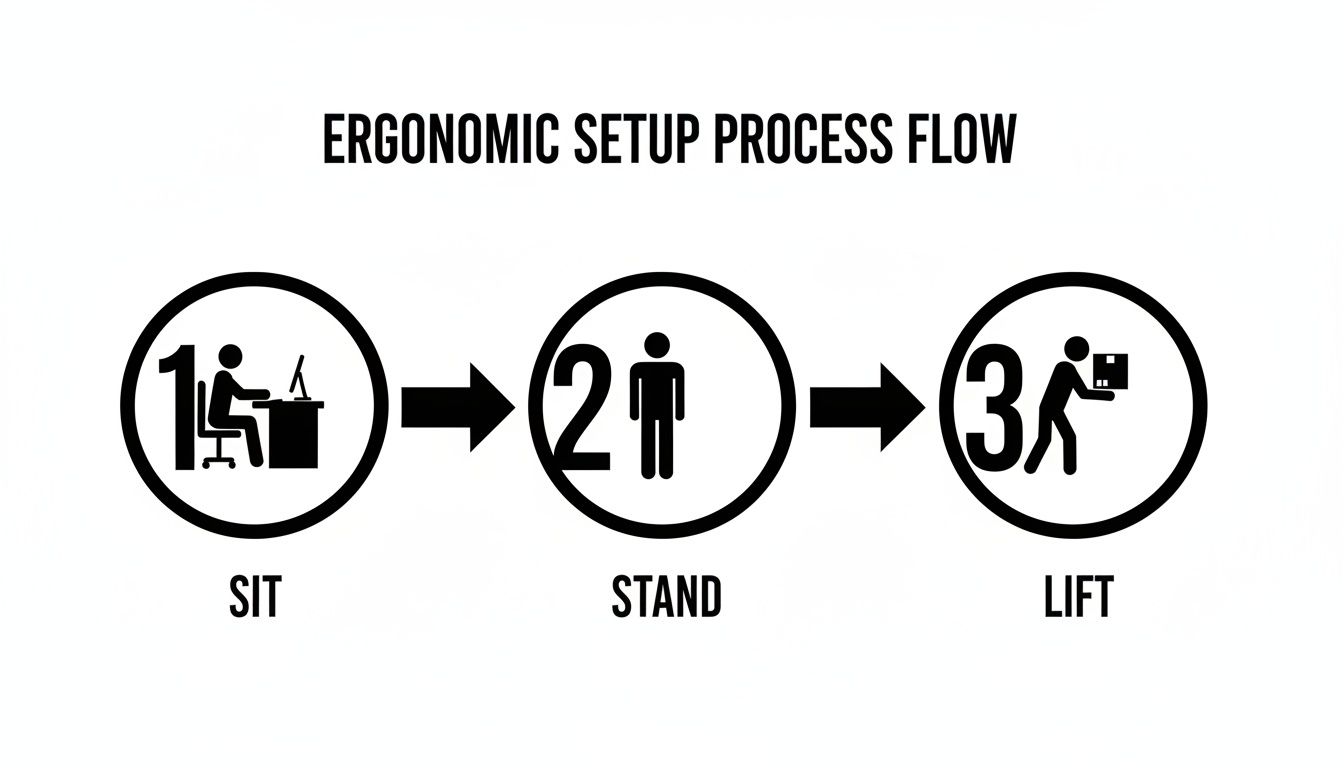

The flow diagram below illustrates how core stability is the foundation for safe movement patterns, from sitting to lifting.

As you can see, a stable core is the active component that underpins safe ergonomics in every position. It directly connects postural awareness with functional strength.

Adding Resistance for Deeper Activation

As your neuromuscular control improves, adding gentle resistance can deepen muscle activation and build endurance in your core stabilizers. Tools like resistance rings provide proprioceptive feedback to refine form and intensify the work.

For example, placing a resistance ring between your inner thighs during a glute bridge forces the adductor muscles to engage. This co-contraction helps activate the pelvic floor, creating a more integrated and stable core engagement that protects the sacroiliac (SI) joints and lumbar spine.

Work-related ergonomic issues and inactivity are silently fueling a back pain explosion. There were 619 million global cases in 2020, projected to hit 843 million by 2050. Pilates is a powerful countermeasure; studies show it can cut the risk of work-induced lower back pain by 35-50% by retraining posture and building the exact core stability needed to offset hours spent at a desk.

The essence of these exercises is control over momentum. A slow, deliberate movement that maintains perfect form is far more beneficial for spinal health than a rushed repetition with a sloppy core.

For those looking to build a resilient core and improve flexibility, a dedicated meditation and yoga retreat can offer a well-rounded approach to strengthening your spine and promoting overall well-being. Ultimately, integrating these targeted, anatomy-aware exercises into your routine provides the active reinforcement your spine needs to stay supported, strong, and pain-free.

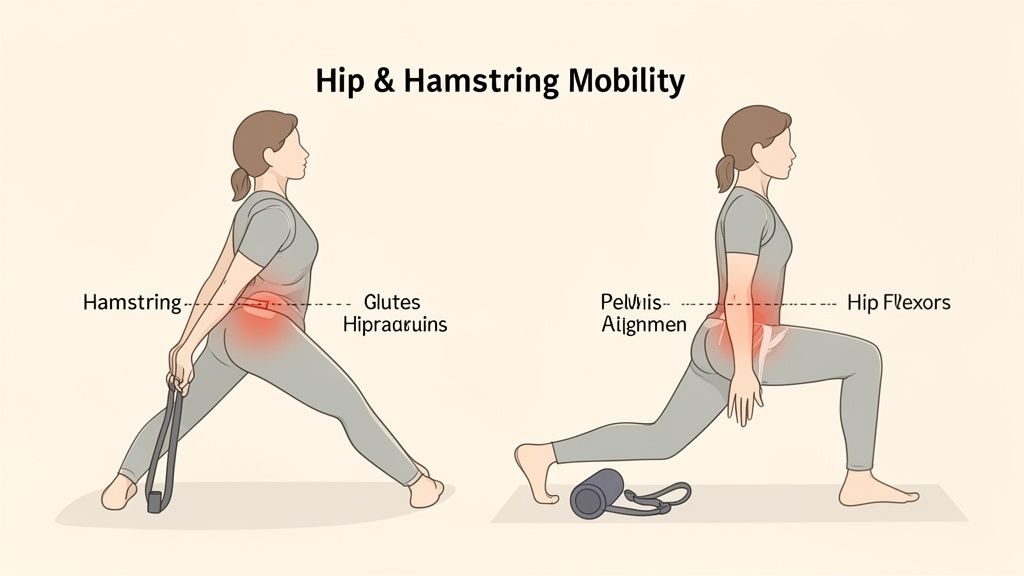

Loosen Up Your Hips and Hamstrings

It's a common mistake to view lower back pain in isolation. Often, the root cause lies in the biomechanics of adjacent joints: the hips and legs. Your pelvis is the foundation upon which your spine sits. If that foundation is stiff or tilted, the entire structure above becomes unstable, forcing the muscles and joints of the lumbar spine to compensate and overwork.

This is a principle of the kinetic chain: dysfunction in one area creates a domino effect. To build a truly resilient back, we must address the mobility of the entire lumbopelvic-hip complex.

Why Tight Hip Flexors Are Your Back's Worst Enemy

Prolonged sitting shortens the hip flexor muscles, particularly the iliopsoas, which originates on the lumbar vertebrae and inserts on the femur. When these muscles become chronically tight, they pull the pelvis forward into an anterior pelvic tilt.

This tilt exaggerates the natural lordotic curve of the low back, leading to compression of the facet joints—the small, stabilizing joints between vertebrae. This sustained compression can cause inflammation, irritation, and pain. Your lumbar spine is essentially being held hostage by your tight hips.

- Kneeling Hip Flexor Stretch: In a kneeling lunge, keep your torso upright and engage your core. Gently shift forward until you feel a stretch in the anterior hip of the back leg.

- Prevent Lumbar Extension: The key is to avoid arching your lower back. Actively perform a slight posterior pelvic tilt (tucking your tailbone) to isolate the stretch to the iliopsoas, not the lumbar spine.

By restoring length to your hip flexors, you allow the pelvis to return to a neutral position. This immediately decompresses the lumbar spine, allowing it to rest in its natural, healthy alignment.

The Hamstring-Glute Connection

Muscular imbalances aren't limited to the front of the body. The posterior chain—your hamstrings and glutes—is equally critical for pelvic stability.

Chronically tight hamstrings, which attach to the ischial tuberosity ("sit bones") of the pelvis, can pull the pelvis into a posterior tilt. This flattens the natural lumbar curve, increasing the load on the intervertebral discs. Simultaneously, weak gluteal muscles (a common issue known as "gluteal amnesia") force the hamstrings and lumbar extensors to overcompensate during movements like walking or lifting, leading directly to strain. Learn more in our article on how to strengthen your hip abductors.

Use Simple Props for Smarter Stretching

Props like a resistance ring or yoga strap can help you achieve a more effective and anatomically correct stretch by providing external feedback.

Using a Strap for a Hamstring Stretch:

- Lie supine: Loop a strap around the arch of one foot.

- Extend the leg: Gently straighten the leg toward the ceiling.

- Maintain a neutral spine: Use the strap to guide the leg closer, but only as far as you can while keeping your sacrum (the back of your pelvis) flat on the floor. The moment your pelvis starts to tilt or your lower back flattens forcefully into the floor, you've lost the isolated stretch.

This technique ensures you're lengthening the hamstring muscle group itself, rather than compensating with lumbar flexion. It's this holistic, anatomy-focused approach that builds a truly resilient back.

Beyond the Mat: Lifestyle Habits for a Resilient Spine

A strong, mobile body is your best defense, but your daily lifestyle choices create the internal physiological environment that either supports or undermines your spinal health. Your exercises build a strong musculoskeletal frame, but your habits are the foundation it rests on.

The Mechanical Load of Excess Weight

From a purely biomechanical perspective, excess body weight places a constant, amplified load on the lumbar spine. Every extra pound of body weight can exert several pounds of additional force on the intervertebral discs and facet joints during dynamic activities like walking. This relentless pressure accelerates degenerative changes and significantly increases the risk for conditions like disc herniation and spinal stenosis.

How Food Fights (or Fuels) Inflammation

Your diet directly influences systemic inflammation. A diet high in processed foods, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats can promote a state of chronic, low-grade inflammation, which can sensitize nerve endings and exacerbate pain perception in the lower back.

Conversely, an anti-inflammatory diet rich in whole foods can help mitigate this. Focus on incorporating:

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Found in salmon, walnuts, and flaxseeds, these have potent anti-inflammatory properties.

- Leafy Greens: Spinach and kale are packed with antioxidants that combat cellular stress.

- Colorful Produce: Berries and broccoli provide vitamins and minerals crucial for tissue repair.

Hydration is also critical. Your intervertebral discs' jelly-like centers (nucleus pulposus) are primarily water. Dehydration can reduce disc height, narrowing the space between vertebrae and increasing the risk of nerve impingement.

The Hidden Impact of Smoking and Stress

Smoking causes vasoconstriction, which severely reduces blood flow to the discs and other spinal tissues. This starves them of the oxygen and nutrients needed for repair, dramatically accelerating the degenerative cascade.

Chronic stress also has a direct physiological impact. The stress hormone cortisol can lead to sustained muscle tension, particularly in the paraspinal muscles of the lower back. This constant contraction can pull the spine out of alignment and create painful trigger points.

Managing stress is a non-negotiable component of spine health. Techniques like deep diaphragmatic breathing or mindfulness can help downregulate the nervous system and break the cycle of stress-induced muscle tension. Some people also explore the vasodilating effects of a sauna for pain relief to help relax tense muscles.

The global link between weight and back pain is staggering. Obesity is a major driver of the low back pain crisis, contributing to 64.9 million years lived with disability worldwide—that's far more than diabetes or COPD. Projections show that by 2036, obesity-linked low back pain rates could hit 125.57 per 100,000 people, with women being hit the hardest. You can discover more about these findings and the urgent need to address this connection.

Your Questions, Answered

Starting a new routine to bulletproof your back always brings up a few questions. It’s smart to wonder about timelines, safety, and the best way to move forward. Let's get into the practical, anatomy-focused answers so you can apply everything you've learned with total confidence.

How Long Until I Feel a Difference?

While better posture and mobility work can give you an immediate sense of relief, building true, deep core strength is a different game. This isn't about the "six-pack" muscles; we're talking about strengthening the muscles that act like an internal corset for your spine, like the transverse abdominis and multifidus.

Most people tell me they feel a real shift in their stability and fewer daily aches within 4 to 6 weeks. That’s with consistent practice, aiming for 3 to 4 focused sessions a week. Remember, we’re playing the long game here—building resilience, not just chasing a quick fix.

The real magic is in consistency, not intensity. A short, mindful session where you truly connect with those deep support muscles is worth far more than a long, grueling workout done with poor form. You're retraining your body's support system from the inside out.

Can I Exercise with Existing Back Pain?

A critical question, and one that requires a careful approach. If you're dealing with mild, general muscle soreness, gentle movement can be incredibly helpful. Think of it as a way to increase blood flow, ease tension, and remind your body how to move correctly.

Start with the most basic, foundational movements, like pelvic tilts or gentle cat-cow stretches. Your body's feedback is everything. If you feel any sharp, shooting, or radiating pain, that’s your signal to stop immediately.

However—and this is non-negotiable—if you have a diagnosed condition or a recent injury, you absolutely must consult with a doctor or physical therapist before you start. They're the only ones who can give you a proper diagnosis and tell you exactly which movements are safe for your body's specific needs.

Is Pilates Better Than Other Workouts for Back Pain?

Every type of movement has its strengths. Yoga is fantastic for flexibility, and weightlifting is a powerhouse for building overall muscle. But when the specific goal is preventing lower back pain, Pilates has a very unique, anatomical advantage.

Pilates is designed to zero in on the deep stabilizing muscles—the TVA, multifidus, and pelvic floor. It teaches you how to keep your spine neutral and your pelvis stable while your arms and legs are moving. This is the exact skill your body needs to protect your back during every other activity you do.

A great approach is often a blended one. Use Pilates as the foundation to build that strong, intelligent core. It will make every other movement you do, from lifting groceries to lifting weights, safer and more effective.

What Are the "Red Flags" I Should Watch For?

The vast majority of lower back pain is muscular. But it's crucial to know the warning signs that could point to something more serious. Think of these as your "red flags" that mean it's time to see a doctor right away.

Get immediate medical attention if your back pain comes with any of these symptoms:

- Fever, chills, or sudden, unexplained weight loss

- Sudden loss of bowel or bladder control

- Weakness, numbness, or tingling that gets progressively worse in your legs

- Pain that is severe, constant, and doesn't get better or worse when you change positions

These can be signs of conditions that go beyond simple muscle strain. Knowing when to self-manage with smart exercises and when to seek professional medical help is a key part of taking care of your spine for life.

Ready to build that deep, supportive core from the comfort of your home? WundaCore provides the expertly designed equipment and anatomy-informed instruction you need to move better, feel stronger, and prevent back pain for good.

Explore the WundaCore collection and start your journey to a resilient spine today.